Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (born Edward James Muggeridge) was a 19th century English American photographer who was a pioneer in the study of motion using photography.

Although originally a landscape and architectural photographer, he is remembered for his study of horses trotting and galloping, the result of being hired by Leland Stanford, a former Californian governor to prove whether all four of a horse’s hooves were off the ground at the same time while trotting.

Later in his career Muybridge would study motion in other animals and humans.

His initial work was performed using a series of cameras, lined up which were triggered initially by a thread that the horse broke as it moved along in front of the cameras, and later by a clockwork mechanism.

Muybridge’s life was not free from controversary.

When a book was written analysing the result of the experiments with horse motion by a friend of Stanford’s, Muybridge was not credited and as a result funding by the Royal Society of Arts was withdrawn and a paper he had written rejected with the accusation of plagiarism.

In 1872, Eadweard Muybridge confronted and shot a man who he believed to have fathered his wife’s 7-month-old son. Muybridge was eventually acquitted on the grounds of justifiable homicide.

Like Edgerton’s work (see below), Muybridge’s work was technically advanced. Banks of cameras needed to be triggered at the exact right moment in order to capture an animal’s motion. Photography was demonstrating that it was very good for capturing those moments which the eye was not good enough or quick enough to capture.

Images like these must have been useful to those arguing that photography was not art but just a way to record events more quickly and accurately than had been available up to that time.

In order to achieve everything that he did in his lifetime, Muybridge had to improve the chemicals that allowed developed film, improve shutter speeds and find ways to capture multiple images of a subject as it moved.

Like Edgerton after him, see below, Muybridge helped to advance the technology and techniques that allowed photographers to freeze or slow time enough that we can capture those things that are to swift to see.

AM Worthington

Arthur Mason Worthington was a physicist who taught at Clifton College in Bristol and the Royal Naval Engineering College in Devonport.

His work on fluid dynamics and, particularly, the study of splashes was instrumental in the development of high-speed photography.

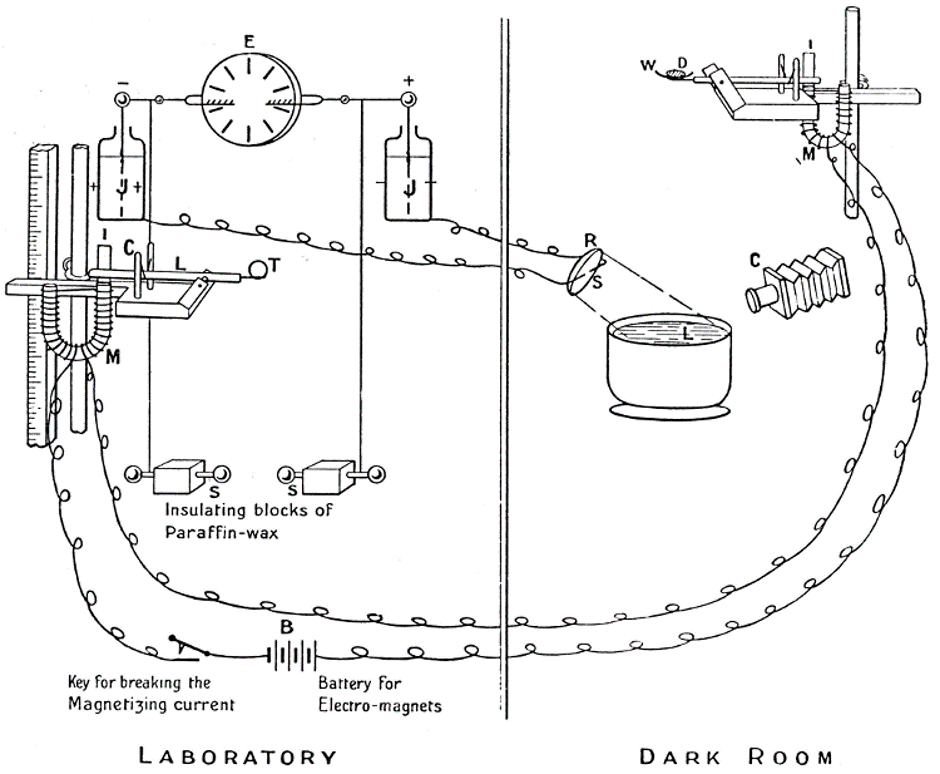

In A Study of Splashes (1908) Worthington details the results of studying items falling into liquids and the splash that resulted. The book contains several series of images captured using a complex setup, including a means of generating a spark to illuminate the splash.

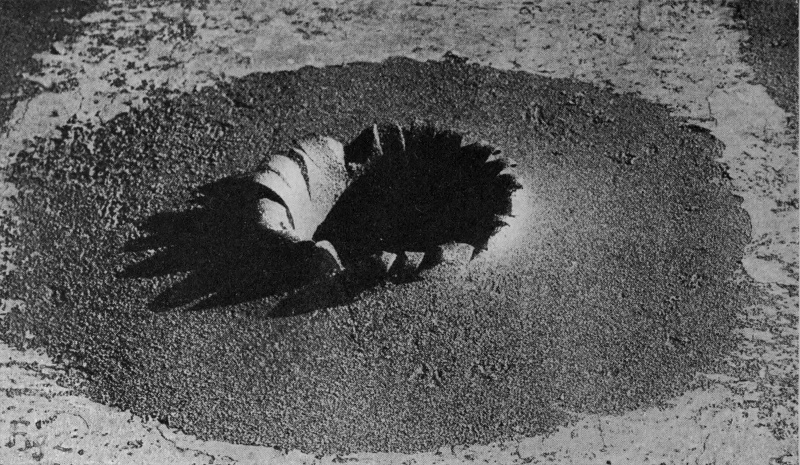

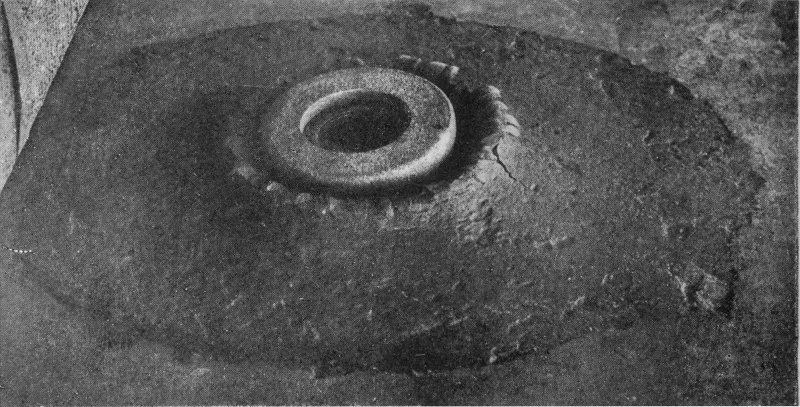

At the start of the book there are two images of “permanent” splashes which are the result of a projectile piercing armour-plate.

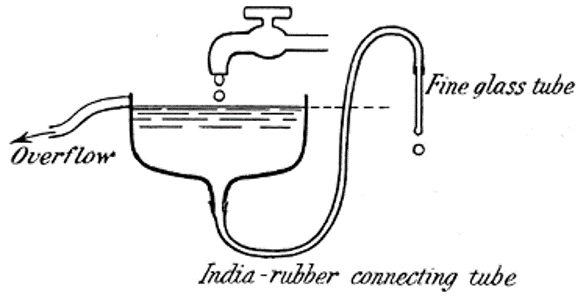

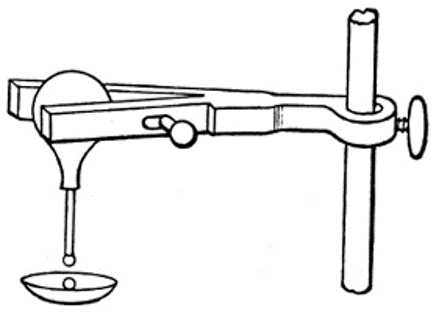

The process of capturing the splashes started with producing a drop of liquid that was to be release from height into the liquid from which the splash would result. The diagrams below show two of the mechanisms that were used to ensure a suitable droplet was produced.

The set up is quite complex and requires careful calibration, especially of the height of the “timing sphere”, a metal sphere which, when dropped will allow a spark to jump between the two magnesium terminals.

Key to diagram:

E is the electrical machine.

J are the Leyden jars whose inner coats are connected to the sparking knobs S.

L is the lever for releasing the timing sphere T.

C is the catapult.

I is the light strip of iron held down by the electro-magnet M.

D is the drop resting on the smoked watch-glass W.

M is the electro-magnet holding down the lever against the action of the catapult, by means of the thin strip of iron I.

C is the camera directed towards the liquid L into which the drop will fall.

S is the spark-gap between magnesium terminals connected to the outer coats of the Leyden jars.

R is the concave mirror.

The images that Worthington captured are remarkable considering when they were made and the technology that was available. Although today we would use similar set ups to release the droplets, triggering the camera and providing a flash to illuminate the splash is a lot simpler with the availability of remote flash triggers and battery powered flashes.

What for Worthington would have been a complex endeavour, and something that rightly deserved the publicity it received, including a Fellowship of the Royal Society, is something that any of us can replicate at home.

Harold Edgerton

Delving into the work of Harold Edgerton was fascinating because aspects of his life resonated with my own.

Edgerton was born on the 6th April 1903. I was born on the 6th April, but over 60 years later.

Edgerton was involved with the development of sonar. I spent 5 years of my career developing software for a sonar system.

Edgerton developed equipment that was used by Jacques Cousteau. I learned to scuba dive while studying at Polytechnic and grew up watching Cousteau’s exploits around the world on television.

Looking through the Edgerton Digital Collection (Harold ‘Doc’ Edgerton (s.d)) reveals a lot of information about Harold Edgerton. It also includes numerous examples of his attempts to freeze motion. The site contains many iconic images.

For some reason the sites owners decided to provide the facility for members of the public to add tags to the images. Some of these are insightful, while others are complete gibberish, or show the maturity of some of the people that have visited the site.

For instance, one of the tags that has been applied to the image of a soap bubble being penetrated by a bullet is “living planet”. This tag is very appropriate because the bubble is reminiscent of images captured from space of the Earth while it is shrouded by night. Lights from towns and cities pouring upwards into the sky. The bullet could be a spacecraft orbiting the planet.

Edgerton’s work developing the stroboscope and his photographs give us an insight into what happens in those fractions of a second that we can’t observe with the human eye. His work as an engineer and applying these techniques when looking at machines give us tools; we can use to study them in the present days. For instance, Edgerton’s work with rotating fan blades and the high-speed images he captured of air flow is something that modern vehicle designers use in wind tunnels to study the flow of air around objects.

Without the work of Edgerton, and people like him, some of the images we take for granted today would not be possible.

Edgerton’s work, also demonstrates that, the development of photography was a major step in the development of human society because of the ways it allows us to study and document the world around us, something that we wouldn’t be able to do if we had to rely on the human eye alone.

This image could symbolise the end of the world, with its inhabitants leaving just as the shockwave from a dying sun reaches the planet.

Although there is a scientific basis to Edgerton’s images, they still allow the human brain to manipulate what the eyes behold and interpret it in ways that are more creative and artistic.

Of all the images that are accessible through the Digital Collection, it is the “Milk Coronet” and similar that are the easiest to reproduce by a modern photographer, without the need for highly specialised equipment or permits for firearms.

Philip-Lorca DiCorcia

DiCorcia’s Heads is Street Photography on steroids, or at least that is what it appears to be when you see the images.

Each of the images has the feel that it was taken at night because of the dark backgrounds. How could the subjects in these images not have noticed a flash going off?

In describing Heads #10. 2002, MOMA adds the fact that the images were taken in daylight to the description provided by the artist in the video, Philip-Lorca DiCorcia – Exposed at Tate Modern (s.d.) of how he captured the images.

Over the years there has been debate about the rights and wrongs of photographing people without their knowledge or their permission.

Walker Evans used a camera hidden inside his coat in order to photograph members of the public using the New York Subway in the late 30s, early 40s. A risky endeavour when you aren’t able to get away from any situation that might arise because someone takes offence to you taking their photo.

Taking photos on public property is not against the law in a lot of countries so DiCorcia’s capturing people’s images although not illegal does open question of whether it is morally right. In the video clip DiCorcia, himself, says that he wouldn’t appreciate someone taking his photograph without his permission but goes ahead and takes other people’s without theirs.

Gefter, Philip (2006) discusses the lawsuit against Philip-Lorca DiCorcia and the implications that a verdict in favour of the plaintiff would have had on both future and past Street Photography.

CCTV cameras, people taking photographs with cameras or on their phones as you happen to be walking by, car dashcams, bodycams, Google StreetView cars, even satellites; we live in a world where our images are captured daily without us knowing it. In few of these examples do we have any right to have our image removed or censored.

Common sense does need to come into any decision to photograph people without their knowledge, or even with their knowledge if they are likely to object violently. If you intend to publish photographs publicly then you need to think about who your subject is and the location where you are taking photographs.

Some people in society are more vulnerable than others, for instance children. It is entirely possible that a child in your image might be in danger from someone, an estranged family member for instance if it was possible to identify their location.

Someone going in or out of a LGBTQ+ venue may end up in difficulty if they are not out to family and friends but are then identified from an image.

Then there is the question of whether you would want someone to take your image or not. If you don’t want someone taking your photo without your knowledge, then you must think hard about why it is OK for you to take other people’s.

Taking photos of people when they aren’t aware of what you are doing, is something I like. I find that, particularly with people I know, it allows me to capture more of the essence of the person. These images can be very powerful, they can also leave the subject vulnerable. I have photos of friends which they don’t like but which I love because the person I know comes through, and not just what they want to show to the world. DiCorcia’s doesn’t have the same level of vulnerability in his images because of the lack of interaction between him and his subjects, but there is still a vulnerability in the images because his subjects weren’t aware their photo was being taken and so may have been letting their guard down in ways they didn’t realise.

Water Drop Photography

There are plenty of examples of water drop photography online. SplashArt have an introduction to their water drop equipment which shows some of the equipment that they supply for photographers who want to explore this area of photography.

The Comprehensive Water Drop Photography Guide – DIY Photography (s.d.) is a detailed guide to which I found very useful when looking at exercise 3.1. The guide covers all the areas you need to consider; equipment, lighting, liquids, colours, focussing and editing.

Final Thoughts

One of the things that the work of Muybridge, Worthington and Edgerton has highlighted for me is that photography has been, and always will be, influenced by the technology that we have available.

Without the ability to capture images quickly, we would not be able to freeze motion. The development of faster shutter speeds, better film development chemicals, flashes and lenses we would not have images such as the ones produced by this trio of photographers. Photography and technology will always go hand in hand as we continue to explore the world and universe around us, but no matter how advanced the technology gets, there will always be the need for human creativity as well as our curiosity as a species when it comes to the images that we capture and how we see them.

References

- (170) Water drop photography tutorial with the SplashArt Kit – YouTube (s.d.) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BuULXOCZSO0 (Accessed 16/02/2020).

- 1877-1895 A.M. Worthington – ‘The Splash of a Drop’ (s.d.) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_g0F_si04A (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- A study of splashes : Worthington, A. M. (Arthur Mason), 1852-1916 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive (s.d.) At: https://archive.org/details/studyofsplashes00wortrich/mode/1up (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Arthur Mason Worthington (2020) In: Wikipedia. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Arthur_Mason_Worthington&oldid=937085436 (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- BOYS, C. V. (s.d.) Drops and Splashes 1. [News] At: https://www.nature.com/articles/078666a0 (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Eadweard Muybridge (2020) In: Wikipedia. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eadweard_Muybridge&oldid=940807056 (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Eadweard Muybridge | Photographer’s Biography & Art Works (s.d.) At: https://huxleyparlour.com/artists/eadweard-muybridge/ (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Gefter, P. (2006) ‘The Theater of the Street, the Subject of the Photograph’ In: The New York Times 19/03/2006 At: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/19/arts/design/the-theater-of-the-street-the-subject-of-the-photograph.html (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Harold ‘Doc’ Edgerton (s.d.) At: http://edgerton-digital-collections.org/ (Accessed 31/01/2020).

- Harold Eugene Edgerton (2019) At: https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/harold-eugene-edgerton (Accessed 31/01/2020).

- Harold Eugene Edgerton (2020) In: Wikipedia. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Harold_Eugene_Edgerton&oldid=938177737 (Accessed 31/01/2020).

- MoMA | Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Head #10. 2002 (s.d.) At: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/philip-lorca-dicorcia-head-10-2002/ (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- Philip-Lorca DiCorcia – Exposed at Tate Modern (s.d.) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bpawWn1nXJo (Accessed 31/01/2020).

- ‘Quicker ‘n a Wink’ (1940) (s.d.) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gspK_Bi0aoQ (Accessed 31/01/2020).

- See The First Time A Photo Proved What The Eye Couldn’t See (s.d.) At: http://100photos.time.com/photos/eadweard-muybridge-horse-in-motion (Accessed 27/02/2020).

- The Comprehensive Water Drop Photography Guide – DIY Photography (s.d.) At: https://www.diyphotography.net/the-comprehensive-water-drop-photography-guide/ (Accessed 16/02/2020).

Leave a comment