The Present – Paul Graham reviewed by Colin Pantall

In Colin Pantall’s review of Graham’s book The Present, Pantall, C. (2012), he highlights how the images presented are the opposite of the decisive moment, so much so that we are left in the position of not knowing what we are looking at.

Pantall suggests that Graham’s images are open to the interpretation of the viewer, that each image allows the viewer to seek out what draws their attention rather than what the artist wanted to draw their attention to.

The presentation of the images as diptychs and triptychs aids this by providing the opportunity to flick between similar images looking for differences.

It’s a bit like playing a game of Spot the Difference but where you haven’t been told how many differences there are.

To fully understand what Pantall is talking about, you need to look at the images themselves. An online image search for “Paul Graham the Present” brings up a number of images from the book as well as photos taken of exhibition installations.

Each of the images that Paul Graham has used are fairly unremarkable, everyday scenes that could have been taken by a tourist. Ordinary people, doing ordinary things.

Each image is different to the others within it’s particular group. In nearly every image nothing remarkable is happening. You could see a similar scene on any street, in any city in the world. Although maybe not at the moment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are, however, exceptions. In one pair of images a group of people are seen walking along. In the second of the pair, one of the people, a woman, has fallen over and some of the others are gathered around her.

The actual moment that she fell has been missed. The Decisive Moment is not shown, whether it was missed accidentally or deliberately, or it was captured but not used does not matter. Instead we are left to witness the aftermath and speculate on the cause. We are left to interpret the image in our own way.

In actuality, using an image of the moment that the lady fell would have undermined the whole approach that Graham was aiming for and which Pantall brings to our attention in his review.

Zouhair Ghazzal

The article the indecisiveness of the decisive moment, decisive moments (2004), was a very difficult read. Not because it is complicated but because the layout of the text makes it very difficult to follow, leading to re-reading parts of the text, or even missing sections because of how the eye follows the text as it moves down the page. Copying it to something like Microsoft Word makes it easier to read and digest.

Ghazzal suggests that overuse of something can result in it being turned into a cliché, no matter who uses it, even Cartier-Bresson.

Capturing decisive moments has become harder to achieve in more recent times as photographers spend more time photographing the same subjects over and over.

The prevalence of selfies, Snapchat and Instagram where the subject tends to be the photographer rather than the environment around them or what is happening in it, supports this idea. The indecisive moment is more important today than the decisive one.

Even in photojournalism we are presented with the aftereffects of events and not the moment that they occur. Cartier-Besson’s image that defines the Decisive Moment or Robert Capa’s image of the Spanish infantryman are rarely seen now. Instead we are bombarded with similar images, telling us the same story over and over.

For decisive moments it is the moving image whether from professional film crews or the person in the street with a smart phone that we can witness Decisive Moments. The moment that JFK was assassinated, the impact of the second aeroplane into the Twin Towers, the collapse of both the buildings. These are images that we are all familiar with, but the still images are single frames from a series of moving ones.

In the case of the Twin Tower, the majority of images were not captured by professionals but by amateurs who happened to be on the ground at the right moment.

Perhaps that is where the future of the Decisive moment lies, not with photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson but with the person on the street, caught up in events who has the presence of mind to take out their phone, hit the camera icon and begin filming.

Ghazzal, raises the issue of taking a series of images, each which on its own might have something decisive about it but when added to a series loses that meaning. How then do we ensure that we continue to show something decisive when we move beyond the single image and into a multiple of images that have a linked or overall meaning? How do we ensure that what is decisive about each image continues to stand out? Is it a simple matter of choosing the images that we use and only picking those where it is possible to discern a moment of importance?

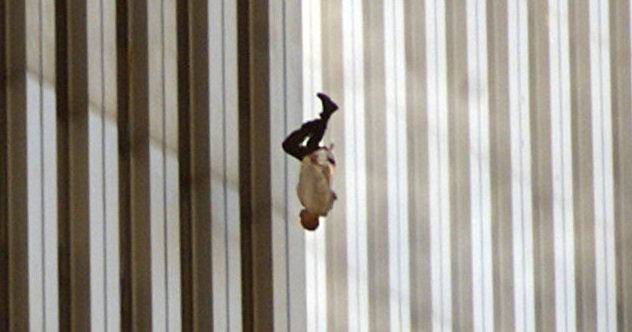

The Falling Man image from 9-11 is iconic, it shows someone who has decided that they would rather jump from a building than burn to death.

By Associated Press photographer Richard Drew

The image is important and shows just how overpowering the need to survive can be but the Decisive Moment, certainly for me, would have been the second that he jumped. At that point he had made a horrific decision and acted upon it. The moment he left the building, there was no way to go back, no way that it would be possible to recapture it.

The same is true of the moment he hits the ground. Until that point he must have been hoping that he would survive the fall, even if the odds were so severely stacked against it. The moment of impact, well, we will never know what his thoughts were, and it is impossible to imagine but that is the moment that a life ended.

H. Cartier-Bresson: l’amour tout court

Watching and listening to such a well known photographer is special. The documentary isn’t just about Cartier-Bresson and his photography but also about several other photographers and the work they do. The documentary title translates as ‘Just Plain Love’ and it is that love of image making that comes across from all involved.

The documentary gave me the impression that Henri Cartier-Bresson was a very vocal and opinionated person. Someone who was very aware of the world around them. A person who was critical of their own work, to the point that he criticises some of the images that a curator of his work as chosen at one point during the film.

I also think that he was also very modest and self-deprecating.

Watching the documentary I found myself drawn to some of the things that he said when discussing photography.

“We live in a privileged world, we don’t have to go to far to see”. The current situation has forced us as students to look at the world around us, we don’t have the freedom to go wherever we want and so have to pay particular attention to things that we might normally have ignored.

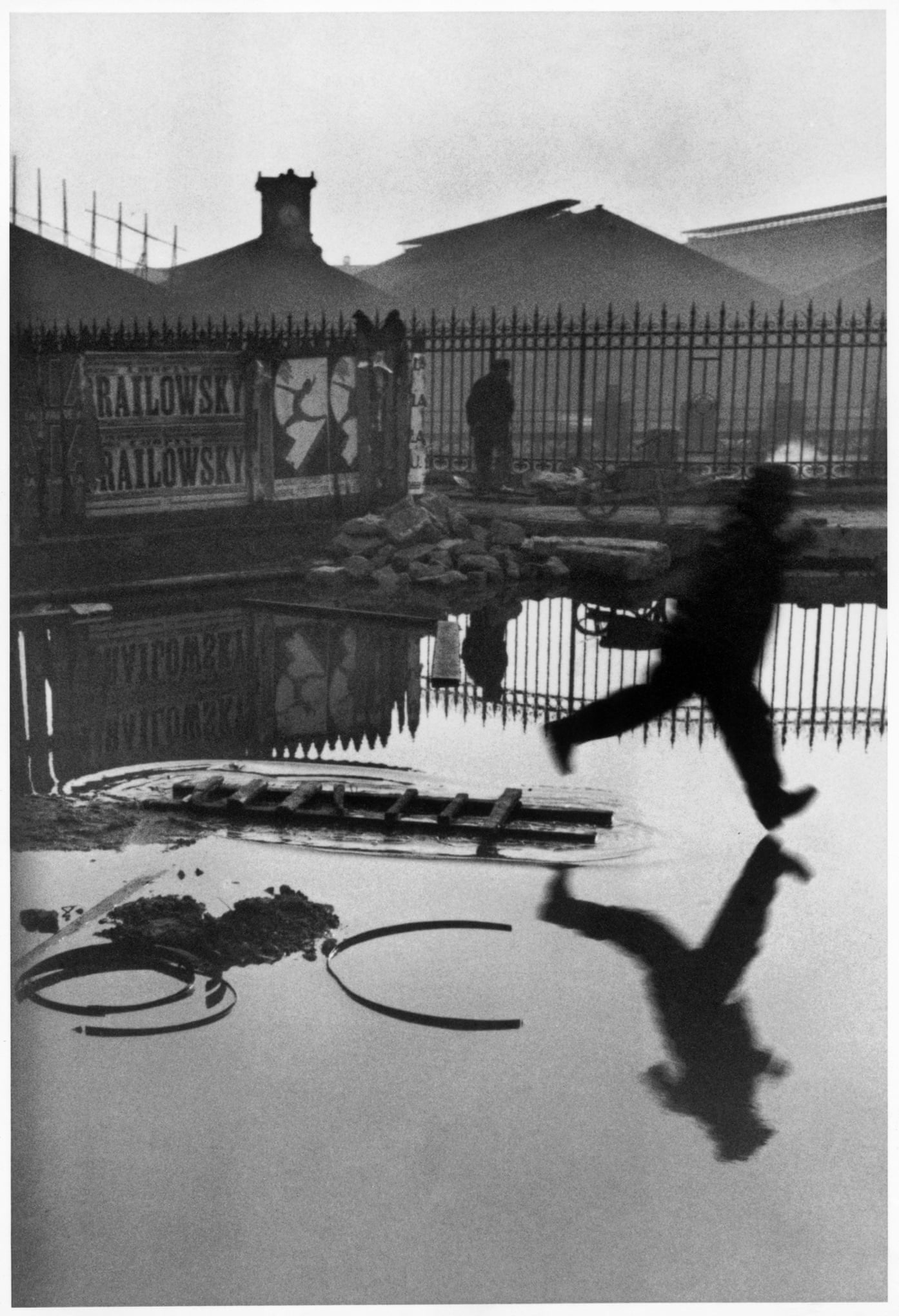

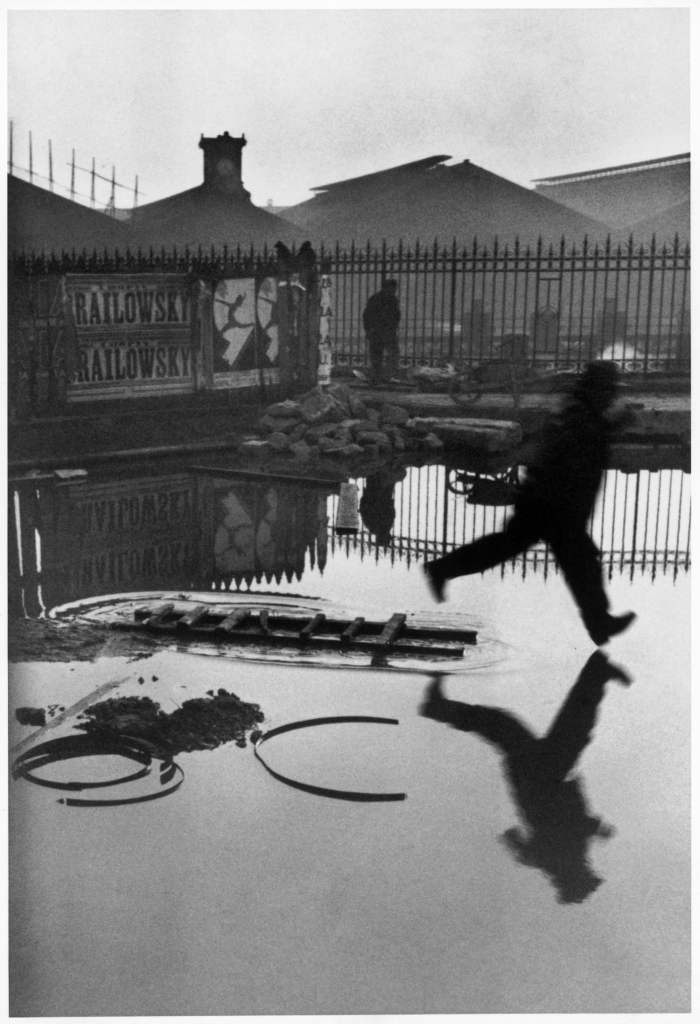

“Its always luck”, “Luck is all that counts”, “If you’re open it will come.” When talking about his photograph Cartier-Bresson says that he didn’t have a clear view of what was happening, he managed to get his lens through the bars but couldn’t frame the image intentionally to get the figure running. Such an important image, an important concept in photography, comes down to luck and pressing the shutter release at the exact right moment.

Photograph: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

In his article, O’Hagan, S. (2014), about Sean O’Hagan says “The decisive moment has come to mean the perfect second to press the shutter.” In 1932, when Henri Cartier-Bresson took this image, and when other photographers like Capa, Taro, Franks, Winogrand and their peers were capturing their images, there was no digital cameras, just film. Capturing the image was, indeed, a matter of pressing the button at the right moment. Today with digital cameras and the ability to set the to capture high speed bursts of images, it isn’t so much a case of pressing the button at the perfect second but being aware that something is about to happen so you can release the shutter and capture a period of time, including the moment what you are waiting for happens.

For Cartier-Bresson “Form comes first. Light is like perfume for me” and that is well illustrated by his photograph taken in Hyères, France. Composing the image, getting the shapes right and then waiting for the right light makes this a great image. Having the cyclist come through just at the right moment is luck, although it is possible to have an inkling that they are coming through, catching them at the exact moment they were opposite the bottom of the staircase is challenging, and requires a large dose of luck.

There are so much that we can learn from Henri Cartier-Bresson but the one, really important, thing that we can learn by watching this documentary is when he says:

“You need to learn to love to look. You can’t look at something you don’t love.”

We do need to learn to do this as photographers and artists. If we can’t look at something because we don’t love it, then how can we expect to capture those Decisive Moments when they happen.

Reflection

By the time I sat down to right up this research I’d already taken the majority of the images I was going to use for Assignment 3. I had an idea of which series of images I was going to use, but finalising this learning log entry has made me reassess that.

In particular Zouhair Ghazzal’s article has made me think about what I was going to submit.

After reflecting on the three sets of images I’d put together I was going to go forward with a series of a cat jumping up on a fence. Ghazzal’s comments about using a series of images made me realise that what I would be showing was a series of decisive moments as the cat jumped but these moments would be lost in the overall idea that it was just a cat jumping. To demonstrate a grasp of the Decisive Moment would mean stepping away from a series of images that tell a story and using a set that show moments that have gone and cannot be captured again. Hopefully my new selection of images will show that.

References

- Conscientious | Review: The Present by Paul Graham (2012) At: http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2012/05/review_the_present_by_paul_graham/ (Accessed 18/04/2020).

- DAILY SERVING » Paul Graham: The Present (2012) At: https://www.dailyserving.com/2012/03/paul-graham-the-present/ (Accessed 23/04/2020).

- decisive moments (2004) At: http://zouhairghazzal.com/photos/aleppo/cartier-bresson.htm (Accessed 18/04/2020).

- H. Cartier-Bresson: l’amour tout court on Vimeo (2001) At: https://vimeo.com/106009378 (Accessed 18/04/2020).

- Pantall, C. (2012) photo-eye Book Reviews: The Present. At: https://blog.photoeye.com/2012/05/photo-eye-book-reviews-present.html (Accessed 21/04/2020).

- PAUL GRAHAM: ‘The Present’ – The New York Times (2012.) At: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/09/arts/design/paul-graham-the-present.html (Accessed 18/04/2020).

- O’Hagan, S. (2014) ‘Cartier-Bresson’s classic is back – but his Decisive Moment has passed’ In: The Guardian 23/12/2014 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/23/henri-cartier-bresson-the-decisive-moment-reissued-photography (Accessed 25/04/2020).